On 23rd May, 2015, the Awami Art Collective launched a public art display at Bagh-e-Jinnah in Lahore to commemorate those civilians who have lost their lives in rampant communal violence and terrorism in Pakistan in the past thirty years.

Drawing its title from a powerful fragment of Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s monumental poem Hum Jo Tareek Rahon Mein Maare Gae (“we who were slated in the dark alleys”), this public art installation which continues till 16th June, combines the efforts of a group of artists, academics and peace activists who feel it is high time that people address the most pertinent of all issues—violence—that plagues the country, nipping its strength and vitality.

The group, referred to as the Awami Art Collective, aims to utilize public space as a means to promote peaceful co-existence and to foster an appreciation of diversity in the country. Some prominent names in the group include Rahim ul Haq, Fareeda Batool, Asad Ali Changezi, Raza, Seher Jalil and Mohsin Shafi whose collaboration turned this innovative idea into a huge success, not only through its compelling theme, but also because of their attempts to promote public art as an interactive medium that intervenes and makes sense of the country’s crisis-laden politics.

Public art in public space

It is the curatorial concept behind the art installation that is commendable. The idea plays on the notion of moving the conversation on violence away from its usual space i.e taking it away from spaces of power, assemblies, discussion rooms and now even galleries, into the urban public space where it is more relevant. The idea is that art should engage not just connoisseurs of artworks and art critics, but people from all walks of life in an act of mourning and remembering those whose ruthless killings have been forgotten in the fabric of time. It is not just about representing a history of violence, but also peacefully contesting it in the public space itself. The concept of the gallery is also redefined, since art as it engages with a certain activism, seeks a public platform where it could provide food for thought to the masses at large.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Want to see a new generation of Pakistani writers? Donate!

———————————————————————————————————————————

Prior to its launch, when this exhibition was being publicized, it was difficult to envisage what it would turn out to be. One isn’t used to public art in a country where free expression is often clamped down and squelched, either by state actors or radical groups. A spate of suicidal bombings in the city space hinders the possibility of launching public gatherings, and those who organize forums for meaningful discussion are immediately considered suspects or security threats by the state.

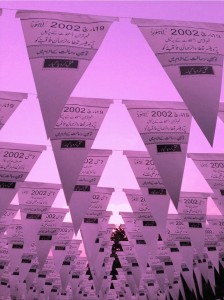

In that context this installation is a bold, path-breaking initiative. It is a move to reclaim public space from violence and use it for productive purposes. The audience at the Bagh-e-Jinnah is asked to participate in the artwork by walking through a circular passage with lines of white triangular flags hanging from the top, each recording a different instance of killing from 1988 till the present. Here, one flag records the Army Public School (APS) attack in Peshawar, while another records the recent killing of Sabeen Mahmud in Karachi. But there are other flags too, that record those killings that have almost been wiped out of the memories of the audience such as the killing of the Olympian boxer, Syed Abrar Hussain Shah, in 2011.

Asad Ali Changezi, a member and organizer of the Awami Art Collective, explained the use of flags as a cultural symbol, being appropriated in this artwork for the purpose of mourning and remembrance: “The jhandi’s (flags) have become a cultural thing in Pakistan. It is incorporated because it is something people can relate to,” he said. The display counts 127 instances of violence, focusing more on killings based on sectarian and ideological differences as well as killings of individuals belonging to a certain profession or political party.

Walking the circle

As just another spectator in the crowd of viewers at Bagh-e-Jinnah, I followed this circular pathway reading the flags and coming back to a point where one is supposed to light aromatic sticks in the centre of the circle. The circular installation emphasizes the repetitive nature of this violent history. As an artist Talat Mehfooz Butt told The Nation, the display mimicked “the circle of life.”

At first glance I thought it would not impact me because it is a common theme. I was wrong; it was not an ordinary stroll. The display is overwhelming. Beginning from the killing of Shias at Jalalabad in 1988, I moved forward towards instances that have taken place in my own time. Killings of several Christians, Sunnis, Shias, Ahmadis, Ismailis, and even Hindus – every community in this country has been subjected to violence at some point in its history and people have been killed brutally. It is then when it hit me. I sensed how, directly or indirectly, I had been impacted by this narrative of violence, how I belong to it. I had just walked through thirty years. It was unnerving. A heavy feeling welled up, making me want to cry. I had simply been fortunate, I realized. Just lucky. I could have been one among the list of the forgotten dead this country has borne, and someone else could have been standing at this exhibition today, reading what happened to me, how it happened to me, and reading my story, trying to imagine the horror of the past in their present. I somehow began to think about the incidents of violence recorded on the flags from the vantage point of my own vulnerability.

Evolving art

In the wake of such an installation by the Awami Art Collective, it is worthwhile considering the evolving face of art in Pakistan as it tries to straddle the predicament of communal violence. What does this display say about the sources that become inspirations for artists? What is the nature of contestation produced by such an installation? More importantly, to what extent can art become a force of revolution in the country?

One way to begin thinking about such questions is to note that art is never neutral to the reality of the environment in which it is produced; a work of art is not just reflective of an artist’s viewpoint, it is a cultural production, an outcome of social and political circumstances that have inspired a meaningful depiction. Pakistan’s scenario for the last three decades (perhaps, even more) is blotted with instances of the most gruesome forms of violence, the most notable being the APS attack in Peshawar that left the country speechless at the site of the massacre of school children. The APS attack is one—albeit a more haunting—case in a series of instances of violence that have shaped the political landscape of the country and perpetuated an economy of fear.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Want to see more art reviews on Tanqeed? Donate!

———————————————————————————————————————————

As terrorism and violence effects the ordinary man, it is not surprising that artists too begin to respond to it. Rahim ul Haq, the mastermind behind this group initiative felt that the ongoing violence in Pakistan is not an offshoot of 9/11. There is a longer history that precedes 9/11 and all incidents of violence need to be perceived within a historical framework. He said: “it is not just the state’s headache to think about the problem of violence. We as citizens of the nation need to stand up and reclaim our public spaces. We need to discard the level of intolerance, the ‘takfiri’ attitude and hatred that is a root cause behind most of the killings that take place.” He went on: “It is about co-existence. It is about cultivating unity in diversity.”

“We who have been slated in the dark alleys” is a reactionary work but also visionary. A visitor at the exhibition states, “It is also a bit too early to refer to it as a movement because it is a product of its time, a response of the artists who feel the need to address this issue and to create that urgency that is the need of the hour. But at least, what one can infer is that the priority of art is shifting. In what direction exactly, one never knows.”

After the rain, the flags are destroyed. A symbolic moment, say organizers. | Photographer: Saman Tariq Malik

Asad Ali Changezi and Raza (organizers of this display) said that the Awami Art Collective plans to launch this exhibition in Karachi and Islamabad in order to increase public exposure. They are also preparing a performance related to the theme. Farida Batool, another leading organizer said: “it is a gradual process but the conversation needs to begin and artists have taken that initiative in the right direction”.

I left the place, with a mixed feeling. There was sadness for what has been lost, for the wounds of those bereaved families that only time may or may not heal. But, on the other hand, there was a slight hope that such initiatives may stimulate individual consciousness, making us own up to our responsibility. Having been to art displays before, this was the most moving experience. Moving because I could relate to it just as everyone else could. Perhaps, the only difference would be that their connection was different than my own. I never thought, I would write about it until only after I had visited the public exhibition myself. The exhibition, as it continues is worth a visit for everyone.

Saman Tariq Malik is a student at LUMS, pursuing a major in English Literature with a minor in History.

I really happy the way Saman writes our efforts of realisation. We just make the art but the writer defines its view of rebirth in society.

Thanks Saman and LUMS.

on point where it comes on creating discourse on violence through art, I think writer does a great job at writing about it. Her personal response was also a heartfelt. Check out her latest article too that i read week ago. I think it was one of the best pieces in the new issue: http://www.tanqeed.org/2015/08/karachi-on-canvas-art-review/

I was introduced to article by a aged friend of mine when I tolded about my visit to the exhibition. I loved it so that I read twice, especially where writer ((Saman)) details how she herself felt. Because that was how i felt too. It is surely a moving article. I am happy that someone really wrote about it capturing it accurately, understanding it for what it was and why we need to remember those who have left us. Hats off to the artists who took this initiative, hats off to the writer indeed for way she writes about it and hats off to Tanqeed for bringing it out to reading audience as well.

mar jao saman

Saman this was beautifully written. I would recommend readers of Tanqeed and art lovers to also check out her latest essay where she takes the paintings of one young artist to think about the penetrative role of city violence in current Pakistani art. Amazing. http://www.tanqeed.org/2015/08/karachi-on-canvas-art-review/

Lovely essay Saman

Saman this is a beautifully written article. Your writing is quite powerful.Wishing you all the best in your future work. Keep shining.

This essay brings forward the need to talk about violence, a subject that we have become so immune to that we hardly register it anymore. Who dies who lives has ceased to lose any meaning for us. yeh ek qaum ka almiaa nahee tau kiya hai. A beautiful essay Saman.

Excellent

I turned back to read this article again a few days back. It was the 16th of December. I had turned to this article because I wanted to read those few sentences of the author that summed up what I was feeling and what the entire nation felt that day. If I were to write something on my feelings, I could say I would be at a loss of words and that usually does not happen. So I think this authors attempt also at explaining what she felt standing and looking at the white flags puts into words an experience that has becomes national in a way. The author writes: ” I sensed how, directly or indirectly, I had been impacted by this narrative of violence, how I belong to it. I had just walked through thirty years. It was unnerving. A heavy feeling welled up, making me want to cry. I had simply been fortunate, I realized. Just lucky. I could have been one among the list of the forgotten dead this country has borne, and someone else could have been standing at this exhibition today, reading what happened to me, how it happened to me, and reading my story, trying to imagine the horror of the past in their present”. Beautifully written. 16th December was when this entire nation mourned a loss that it will never recover from. The burden is heavy. It takes a man to write and confess that ‘I cried’. Sure why not? We need to cry…we need to cry because they were humans…we need to cry because we are humans too. Impactful article