Issue 7 Essay | Get the full digital print edition now!

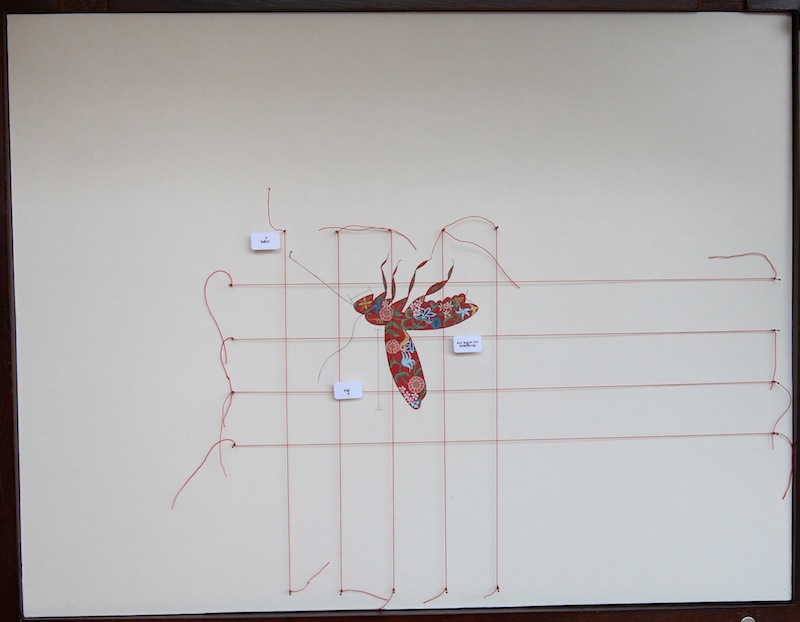

Artist: Tazeen Qayyum | “Test on a Small Area before Use III”

1000 Subscriber Campaign

Help us get 1000 subscribers!

Last year, you helped us raise over $10,000!

That helped us begin to build TQ.

This year, that effort continues.

Help us sustain TQ.

[purchase_link id=”7407″ style=”button” color=”green” text=”Subscribe”]

Thank you!

Please click on the tip jar and donate!

$25 or over and we’ll send you our

first digital print copy.

[schedule=’2014-09-24′ at=”00:01″]

Sidebar

“Justine Smith critiques the prevalent project within Native studies of replacing Western epistemologies and knowledges with indigenous epistemologies as a project unwittingly implicated in a pro-capitalist and Western hegemonic framework. She argues that the framework of ‘epistemology’ is based on the notion that knowledge can be separated from context and praxis and can be fixed. She contests that a preferable approach is to look at indigenous studies through the framework of performativity–that is indigenous studies focuses on Native communities as bounded by practices that are always in excess but ultimately constitutive of the very being of Native peoples themselves (Smith 2005). The framework of performativity is not static and resists any essentializing discourse about Native peoples because performances by definition are never static” —Andrea Smith Native Americans and the Christian right: The gendered politics of unlikely alliances.

“Myths and theories of liberation have been constants in the long record of human experience. They are the bracing concomitants to impositions of domination and oppression, whatever the form of a particular regime. And even when the recorder of the moment was unsympathetic or downright hostile to even the most fugitive and muted affirmation of human integrity, there has been almost inevitably at least a trace, a hint, of the desire for a just order.” — Cedric Robinson Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Political Tradition

With each historical moment, however, the rationale and cultural mechanisms of domination became more transparent. Race was its epistemology, its ordering principle, its organizing structure, its moral authority, its economy of justice, commerce, and power. — Cedric Robinson Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Political Tradition

“If the productivity of the capitalist family and the female body was centered on the production of children, then women’s liberation required that we break with this imposition, with being condemned to this sole function, with the fixation of this role. Hence the slogan: “Women let’s procreate ideas not just children!” This was a cry of liberation from biological determination, an invitation to a different creation, to procreate ideas that could generate another world in which the mother-wife function would not constitute any longer our only possible identity, or be paid at the cost of so much toil, isolation, subordination, and lack of economic autonomy. This is why we put forward the demand for wages for housework, to reject its gratuitous attribution exclusively to womankind, so that women’s economic autonomy might be constructed starting from the recognition of that first work.” — Maria Rosa Dalla Costa. 2012. “Women’s Autonomy and Remuneration for Care Work.” The Commoner. 15: 198-234.

Racism is “state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” — Ruth Gilmore The Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis and Opposition in Globalizing California.

“For may British officials, India was a vast collection of numbers. — Bernard Cohn Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge

“In the eyes of many colonial administrators in the nineteenth century, the advance of science and the advance of colonial rule went hand in hand. Science helped to secure colonial rule. to justify European domination over other peoples…” — David Gilmartin. 1994. “Scientific Empire and Imperial Science.” The Journal of Asian Studies. 53(4): 1127 – 1149

“The modern state can barely function without becoming involved with racism at some point, within certain limits and subject to certain conditions.

What in fact is racism? It is primarily a way of introducing a break into the domain of life that is under power’s control: the break between what must live and what must die…

Racism also has a second function. Its role is, if you like, to allow the establishment of a…relation of this type: ‘The more you kill, the more deaths you will cause’ or ‘The very fact that you let more die will allow you to live more.’…[or] ‘The more inferior species die out, the more abnormal individuals are eliminated, the fewer degenerates there will be in the species as a whole and the more I–as species rather than individual — can live, the stronger I will be, the more vigorous I will be.’…

This is not, then a military, warlike, or political relationship, but a biological relationship. And the reason this mechanism can come into play is that the enemies who have to be done away with are not [considered] adversaries in the political sense of the term; they are threats, either external or internal, to the population and for the population.” — Michel Foucault Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976.

“When I say ‘killing’ I obviously do not mean simply murder as such, but also every form of indirect murder: the fact of exposing someone to death, increasing the risk of death for some people, or quite simply, political death expulsion, rejection, and so on.” — Michel Foucault Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976.

“Referring to…the phantomlike world of race in general, [Hannah] Arendt…suggests that the politics of race is ultimately linked to the politics of death. Indeed, in Foucault’s terms, racism is above all a technology aimed at permitting…. ‘that old sovereign right of death’.” — Achille Mbembe “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15(1): 11-40.

“Colonial occupation itself was a matter of seizing, delimiting, and asserting control over a physical geographical area — of writing on the ground a new set of social and spatial relations. [This was]….ultimately tantamount to the production of boundaries and hierarchies, zones and enclaves the subversion of existing property arrangements; the classification of people according to different categories; resource extraction; and finally, the manufacturing of a large reservoir of cultural imaginaries. These imaginaries gave meaning to the enactment of differential risks to differing categories of people for different purposes within the same space; in brief, the exercise of sovereignty. Space was therefore the raw material of sovereignty and the violence it carried with it. Sovereignty meant occupation, and occupation meant relegating the colonized into a third zone between subjecthood and objecthood.” — Achille Mbembe “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15(1): 11-40.

For further reading

Ansari, Sarah. 1992. Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind,1843-1947. Vol. 50. Cambridge University Press.

Banaji, Jairus. 2003. “The fictions of free labour: Contract, coercion, and so-called unfree labour.” Historical Materialism 11.3: 69-95.

Dalla Costa, Mariarosa. 2012. “Women’s Autonomy and Remuneration for Care Work.” The Commoner. No. 15. pp. 198-234

Foucault, Michel. 2003. Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976. Vol. 3. Macmillan.

Gazdar, Haris, Ayesha Khan, and Themrise Khan. 2002. “Land tenure, rural livelihoods and institutional innovation.” Collective for Social Science Research, Karachi (2002).

Gilmartin, David. 1994. “Scientific Empire and Imperial Science: Colonialism and Irrigation Technology in the Indus Basin.” The Journal of Asian Studies. 53(4): 1127-1149

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2007. The Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis and Opposition in Globalizing California. University of California Press.

Khan, Maliha. 2007. The Political Ecology of Irrigation in Upper Sindh: People, Water and Land Degradation. ProQuest.

Martin, Nicolas. 2009. “The political economy of bonded labour in the Pakistani Punjab.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 43(1): 35-59.

Mbembé, Achille. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture 15(1): 11-40.

Mignolo, Walter. 2002. “The geopolitics of knowledge and the colonial difference.”The South Atlantic Quarterly 101(1): 57-96.

Mumtaz, Khawar, and Meher M. Noshirwani. 2006. “Women’s Access and Rights to Land and Property in Pakistan.” International Development Research Centre.

Smith, Andrea. 2008. Native Americans and the Christian right: The gendered politics of unlikely alliances. Duke University Press.

Zaidi, S. Akbar. 1991. “Sindhi vs Mohajir in Pakistan: Contradiction, Conflict, Compromise.” Economic and Political Weekly. 1295-1302.

Why Tanqeed?

“Because it is the only truly critical and humanist publication coming out of Pakistan!” —critic

Why Tanqeed?

“If you want just information, go to any other news source. But if you want perspective, if you want understanding, Tanqeed.org is the place to go.” —novelist

Why Tanqeed?

“Tanqeed stands for a critical challenge to both conventional wisdom and preconceived ideas about the state, the society, the history and the culture in Pakistan. It partakes in a fearless debate treating nothing as sacred or taboo.” —editor

Why Tanqeed?

News from Pakistan is easy to find. Its vibrant press produces newspapers and magazine, websites and news channels. But what lacks in much of this media ecology is the long-view, the attempt to place today’s events in a historical context or to widen the framework to bring culture and society into a political story. Tanqeed’s reason for existence is to bring the historical and the cultural into a conversation with the political. For that, it is indispensable. —professor

Poni Kohlan sent her husband to collect their wages from the landlord when she heard about another worker’s husband who was killed for protesting the rape of his wife. It had become apparent that the incident was the rule rather than the exception: The stories of women who were raped and husbands who were punished had begun to pile up, and the police that would show up afterwards would fail to do anything about it. No work was worth risking the violence that permeated the lands she had helped to till, and she had decided it was time for her family to leave. However, by the time her husband approached the manager to collect their wages, she realized it was too late: They were owed nothing, they were told, because they were in debt. “We were shocked but could not do much in the presence of their armed guards. I became certain we would not be able to escape the landlord’s prison and abuse,” she says. “We felt like we were trapped in hell.”

Poni Kohlan is one of an estimated 1.7 million agricultural workers and sharecroppers who work in Pakistan’s Sindh province. Better known as haris, the majority of these workers are — like the Kohlan family — in debt bondage, and live in some of the province’s poorest districts, including Thatta, Dadu, Badin, Mirpurkhas and Umerkot. Women like Poni are exposed to brutal levels of sexual violence: Armed with a coterie of contractors and armed guards, the landlord and those who stood by him began to rape Poni after her and her family tried to leave, an assault she decided to endure to keep her loved ones safe.

To date, the debate around bonded labor in Pakistan — or, indeed, around the world — has been relegated to the exceptional. Slavery, it is argued, is an anachronism with no place in the modern world, which is why its existence is limited to the backwards, rural hinterlands of third world countries like Pakistan. For those with a more patriotic bent, its continued existence is a black spot on the face of the modernizing nation of Pakistan, and one that requires the hard and fast upholding of law and order. Slavery is, after all, illegal.

In this essay, I will argue against the idea that slavery is a thing of the past, or that it has no place in our modern world. Following in the footsteps of thinkers like Andrea Smith, I use testimonies of women who have escaped bonded labor in Sindh to understand their own oppression. In this way, I render visible their epistemic authority, or the authority of their knowledge: They know what is happening to them. In Smiths’s introduction to her book, Native Americans and the Christian right: The gendered politics of unlikely alliances, she writes that rather “than studying native people so we can learn more about them, I […] illustrate what it is that Native theorists have to tell us about the world we live in and how to change it.” A closer look at their stories reveal that women who have escaped bonded labor simultaneously narrate stories of incarceration for the forced extraction of labor, and articulate their desires, dreams and escapes to freedom. Although their oppression seems all-encompassing, it is important to recall the scholar Cedric Robinson’s reminder that their incarceration is but one condition of their existence. In fact, these women’s impulse to freedom in the face of extremely dehumanizing conditions is the consequence of the “dialectic between power and resistance to its abuses.” This resistance is “located in history and the persistence of the human spirit,” and exercising it is likely the only form of emancipation from their inhumane existence.

Modern-day slavery is a product of actually-existing capitalism, and the state facilitates and sanctions its existence by exercising its control over the life and death of its citizens for the sake of capitalist accumulation.

Women working for large landholders in Sindh, like Poni Kahlan, make capitalist accumulation possible. Indeed, the activist Maria Rosa Dalla Costa has pointed out that the labor within their homes provide conditions for reproducing, maintaining and caring for the regeneration of an incarcerated laboring class. For a long time, social theorists have understood bonded labor as a thing of the past, at most persisting in areas still stuck in pre-capitalist, feudal modes of production. Over time, however, many social theorists have come to accept that bonded labor is, actually, completely congruent with capitalist production (Brass 1994). Moreover, they argue, like Cedric Robinson in Black Marxism, that capitalism has always been racialized capitalism, not only because it has used cheap or slave labor for its development, but because slave labor, colonization and racialized hierarchy is seen as a necessary component of capitalism. It is nearly impossible to disaggregate development, modernity and the expansion of capitalism from colonialism, expansion and slavery. In fact, those processes created the conditions of possibility for capitalism’s present-day formation. That is why it does not make sense to understand bonded labor ahistorically — without a serious understanding of the past, and the conditions, institutions and structures created in Sindh under the British.

Colonial roots

When the British annexed Sindh to consolidate their power, they were in the process of mapping India, historically and culturally. The latter meant that the British administrators began to invent and then classify Indians according to various categories including language, tribe and class. Historians and scholars have written extensively about this. See for instance Bernard Cohn’s Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge and David Gilmartin’s article, “Scientific Empire and Imperial Science: Colonialism and Irrigation Technology in the Indus Basin.”

Land settlement was crucial to establishing British political and economic control so the British doled out large land grants to members of the elite like zamindars (landowners), pirs and their family members in exchange for their support of British rule. British colonialism, with its attendant notion of enforcing a state-sanctioned legal regime of private property ownership that benefitted and rewarded people who would support their rule in terms of providing military and tax-paying support, guaranteed an ossification of power of the landed people while trade, extraction of surplus value and market oriented setup ushered in capitalist relations.

In their censuses, the British distinguished between land-owning and land-working castes. Even though this division existed within the village economy, the effect of the British recoding it hardened these relations further. The peasant classes were stuck within their caste boundaries and classifications, which solidified their landless status. Thus the institutions created, sustained and propagated by the British to consolidate their power had a lasting impact in terms of power, wealth, resource distribution and social division between the landed classes and the landless peasants.

Subsequently, land ownership became critical for subsistence and even survival of peasant farmers, from whom communal forms of control and use had been divested by the new regime of private property. Before private property laws, peasants could settle and clear new land with or without a landlord’s help. But, when the British appropriated excess land as state land and tied the right of occupancy to property ownership, they created a system where landowners could now flout long held customs which would have given the landless rights.

These structures survived into modern-day Pakistan. After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, Sindh became one of the provinces of Pakistan with a large agricultural base, second only to Punjab. The partition of India triggered the en masse migration to Sindh of Muslims from central Uttar Pradesh, Central Pradesh and other Muslim minority areas in India. This caused a demographic shift in the metropolis of Karachi and deep tensions within the existing nationalist and migrant ethnic communities. The Sindhis felt domination from Punjab as the majority province, from Punjabi settlers in Sindh and the Urdu-speaking migrants who settled in major cities, including Hyderabad and Karachi. These groups were also over-represented in state institutions since they were part of the literate classes.

As agro-capitalism developed in Punjab, thanks to the Green Revolution, the Punjabi elite came to dominate the political scene at the center. By the 1980s, the resentment in Sindh had grown to a point of secessionism; the movement was quelled by the largely Punjabi and Pashtun dominated army. Since then there has been a deployment of largely Punjabi troops through much of interior Sindh, coupled with land allotment to Punjabi army officers in Sindh.

The political machinations of the center and the rise of nationalism in Sindh did nothing to upset the imbalance of land and power distribution in rural Sindh. If anything, it bolstered the power of the landlords and or pirs as they claimed to represent to the center the interest of Sindh. Rural Sindh remained largely dominated by Sindhi and Punjabi land-owners who, over time, consolidated their social, economic and political power by dominating representative politics. The non-ownership of land has become a significant factor in Sindh where, according to a joint study by Khawar Mumtaz and Meher M. Noshirwani, “two-thirds of rural households [do not own] any land and just 0.4 percent of households [account] for nearly 24 percent of the total area.” This was true of farmers as well as haris or landless sharecroppers.

The conditions within which people like Poni Kohlan function links back to a system where agricultural workers do not own land. These conditions were first set up by British colonial powers, and carried forward by the independent postcolonial state into the era of neoliberal capitalism, making forced labor, debt bondage and incarceration of landless peasants possible.

Marvaan Kohlan | Fouzia Saeed & Veerji Kohli. 2007. Women in Bondage: Voices of Women Farm Workers in Sindh

Marvaan Kohlan and her family were landless peasants who worked for different landlords to earn a modest living. Though it was not much, it was enough to get by on. The problems first arose when they started working for a new landlord on the recommendation of a relative. They built their huts on his lands and he promised to pay them wages and give them food in return for their work, but they never got paid their full compensation. One day, her husband went to ask for the wages in full. The landlord initially deflected the question and then finally said that, in fact, they were indebted to him. Once he claimed that they owed him, and not the other way, he unleashed his wrath.

“We were totally enslaved,” says Marvaan. “There was a high fence around our huts, leaving only one way to get out. This is where the managers used to sit.” Marvaan and the other workers were told that if they tried to escape they would be killed. For twenty-two years, Marvaan and her family worked for the landlord. During that time, there was no recourse to the police because, to Marvaan, they all seemed to be too friendly with each other. The overseer who took the women out to the fields declared that they were all his “wives” while they were out on the field. If any of them sat down because they were exhausted, the managers kicked them to make them go back to work.

One day, some of the laborers escaped and filed a case with the police against the landlord. The police came to the property and removed the complainants families. The overseers told Marvaan and the others that the laborers would be back but they never returned. In fact, the remaining laborers were now terrified of the police who were asking for their testimonies. They did not know the consequences so they refused to talk to them. When they realized that those laborers had actually been liberated, they regretted not cooperating with the police.

Eventually, the liberated laborers came to visit Marvaan’s family and the managers were so angry that they brutally beat her husband. She was not allowed to take him to the hospital and, even if she had, she did not have the resources to cover his medical expenses. She could not do anything but wait.

“On the eighth day, he passed away. I didn’t know how to handle a shock of this magnitude. I had his murderers in front of my eyes and could not do anything. The day my husband died, I decided that no matter what, we had to leave that place somehow.”

Veeru Kohli | Testimony from Book: Fouzia Saeed & Veerji Kohli. 2007. Women in Bondage: Voices of Women Farm Workers in Sindh

Veeru’s father loved her deeply. He was always concerned about her happiness and well-being. He picked out a good family for her to marry into and she did, but they did not know that the family was mired in concocted debt and worked for a landlord under conditions of poverty in bonded labor. They struggled and worked tirelessly for this landlord for seventeen years and finally made their way out of his farm to work for another landlord. They hoped that this would be a better situation in terms of regular pay, and not having to be bonded. But, much to their disappointment, this landlord turned out to be worse. At the new farm, the women were always surrounded by guards who threatened them and physically beat up the men-folk in front of their wives to instill fear. One day, when Veeru’s son was getting married, the landlord passed by and demanded to know who had granted her son permission to get married. When he did not receive an answer that satisfied him, he began to beat the bride and groom. Faced with his power and authority, Veeru felt helpless. And even though she cried and screamed, she was pushed away.

The landlord and his managers were ruthless. They would physically abuse the haris (landless sharecroppers) without any provocation. Once they started beating Veeru’s son and she retaliated, hitting the manager back. The manager did not take kindly to this at all and reported it to the landlord. Veeru told her son and daughter-in-law to run away, suspecting that the landlord would strike out against them. Sure enough, the next day the landlord came over and demanded that Veeru hand over her daughter-in-law. She refused, and said that they had left. He was livid. He asked his guards to bring Veeru to him the following day in place of the daughter-in-law.

Afraid for herself yet happy that she had managed to help her son and his wife escape, Veeru was preparing herself for abuse and torture when it occurred to her that she could also try to escape. The next day as the women left for work, she went with them but surreptitiously slipped away towards the road. She ran as far as she could and only stopped when she reached the safety of her brother’s home.

At her brother’s house, she started to plot to get the rest of her family out. She collected the 60,000 rupees that was her putative debt and sent relatives to him to free the rest of the family. The landlord said that Veeru owed him Rs. 800,000, and that he was going to sell the women of her family to get that money back.

Devastated by this news, Veeru sought another solution. She heard about the camp of haris who could possibly help. “These people […] were freed from similar prison-like circumstances that I had been living in. They referred to anyone who was fighting actively for justice as a ‘comrade’. I told comrade Lali’s mother what I was trying to do for my family […] She said ‘We are all with you and will help you get the rest of your family liberated’. I felt relieved.”

She stayed in the camp for a while, where resources were gathered and a letter was written regarding her circumstances by the Human Right Commission of Pakistan, an independent watchdog NGO. She approached the police alone with the letter and had to wait for three consecutive days without food afraid that since she was near the landlords farms his people would capture her anytime. Finally, on the third day she met with the officer in charge and gave him the letter, telling him her entire story. He agreed to go with her to free her family.

“The guards saw us coming from a distance and fled. I thought to myself that those who roamed around like lions, treating us brutally, are now running away like mice. I felt brave. I was thrilled to see my children and other family members. They were shocked and could not believe how I had brought such senior police officers with me. They could never imagine that I would be able to mobilize support, much less such high level police support.” (Saeed et al 2007: 22)

Once freed, she and her family moved around from camp to camp and in that process, she decided “that I would contribute to somehow making this problem go away. I felt strongly that this kind of abuse of poor farming labour was too much. Though most of the people suffering in this hell were from my Hindu community, there were some Muslims also.”

Veeru Kohli worked for a number of organizations to raise awareness, traveled to India and in the 2013 elections, she ran for local office on the platform of eradicating bonded labor.

Women speak of high walls surrounding their dwellings, guards stationed at the single exit from those dwelling, and the continuous monitoring of movement: The experience of bonded labor is like the experience of being imprisoned, or incarcerated. Every day, these women experienced threats of violence, actual physical and sexual violence and exhaustive, uncompensated labor. The guards, the contractors and the landowners, in collusion with the police, oppress these women through beatings, rape, intimidation, neglect and murder. Subject to extreme forms of gratuitous violence and threatened with concocted irredeemable and ever-growing debt to extract their labor and compliance, these women resist these oppressive carceral conditions through protest, escape and collusion to free others like themselves. These women have dreams of freedom that they realize with the help of members from their communities who have escaped, non-governmental organizations and some state actors.

The institutional structures of the state of Pakistan support the landowners’ abuses: for example, on paper the Pakistani state has legislated against bonded labor under the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1992 [Pakistan] but implementation is lax or largely ineffective since the landowners become the face of the state in the executive, judicial and legislative branches at the provincial level. Similarly the Sindh Tenancy Act mandates that certain part of the produce ought to be given to the tenants who work the farm but this is also not implemented. Some theorists contend that this can be due lack of democratic development in Pakistan, which has seen military dictatorship for half of its life. Others fault the lack of positive discrimination for disadvantaged groups, comparing the case to India which has legislated affirmative action for lower caste groups, including landless peasants.

Incarcerated at home

In Pakistan, which shares the same class and caste structures as India, women landless peasants represent a class, a caste, and a religious group that is exposed to state racism that views them as inferior and regimes of control that create the conditions possible for deprivation, discrimination and incarceration for the extraction of their labor power. The state apparatus wants to expel them from the body politic; at the same time they are required to subtend the needs of the body politic (constituted by the landed class) by providing free labor. As the French philosopher and well-known theorist of modern forms of governance Michel Foucault has explained, racism is necessary for the modern state because part of the work of modern forms of governance is exactly to decide which people count and which don’t. The British colonial state in Sindh sowed the seeds of state racism through its classification systems and regimes of control which fixed certain categories of people permanently below others.

In post-partition Pakistan the imperatives remained similar with the maintenance of this underclass as represented by these women carceral laborers and their families whose rights, freedoms and existence were completely dispensable, but whose labor power was crucial in so far as it could support the hyper life to the landed elites. This is a kind of a death, Foucault once argued, because the state attempts to strip these laborers of their rights and to expel them from the body politic. They are not considered full citizens and thus exposed to daily risks in their lives to which the people who count are not. The African scholar Achille Mbembe has used Foucault’s framework in the context of describing the territorial hierarchies that existed in townships in apartheid South Africa where black landownership was made illegal except in reserved areas. Although Pakistan is not an explicitly apartheid state as South Africa, the similarity with the African situation is enlightening. Justifications once given by the colonizers are now proffered by the landlords where these farms becomes spaces where peasants occupancy rights are made illegal, where they are exposed to high risk situations — all in the name of creating civilization.

These women laborers are resisting such state-sanctioned regimes of labor extraction and control. Their acts of resistance are a testament to their endurance. The stories of the women sampled here demonstrate the urge to a livable life, that motivates those enslaved in even the most dehumanizing conditions. Veeru Kohli freed her family, freed herself and then went door to door to canvas for her platform of the eradication of bonded labor and the freeing of all laborers. She saw a vision of freedom for the entire community and her vision garnered her national acclaim in Pakistan and 3000 votes in her constituency. While this was not enough to elect her to office, it was enough to show her community and the people that resistance is possible and a livable life realizable.

* * *

Sarah Suhail is a doctoral student in women and gender studies at Arizona State University, learning about the freedom dreams of those situated in structures of organized violence, particularly in conditions of unfree and coerced labor in Pakistan. She works with peasant, fisher-folk and queer movements in Pakistan and on a number of issues regarding intersectional oppression and the politics of resistance. She is from Lahore.

[/schedule]

[…] even if the consequence, this time, was to block the privatization of that asset. Sarah Suhail uses racism as a conceptual framework to discuss women’s bonded labor in Sindh. While these […]

[…] last week’s releases from our Fall 2014 issue? neoliberalism against privatization and how the state sanctions bonded labor and islamabad’s lost […]

How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor http://t.co/wf1D8C0Ql7

#Slavery is intrinsic to modern-day #capitalism. #Pakistan #postcolonialism

RT @TanqeedOrg: JUST PUBLISHED! How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor | Sarah Suhail

Slavery is intrinsic to modern-day… http://t.co/KvxJ…

#Pakistani women #laborers are resisting #capitalist, state-sanctioned regimes of #labor extraction and control. http://t.co/4lKDt1Apdl

RT @TanqeedOrg: #Pakistani women #laborers are resisting #capitalist, state-sanctioned regimes of #labor extraction and control. http://t.c…

How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor http://t.co/sUYtMKr7hP

‘How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor’ Sarah Suhail’s article in @TanqeedOrg http://t.co/9UujyJHNcy

RT @booksconnect: ‘How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor’ Sarah Suhail’s article in @TanqeedOrg http://t.co/9UujyJHNcy

RT @booksconnect: ‘How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor’ Sarah Suhail’s article in @TanqeedOrg http://t.co/9UujyJHNcy

How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor http://t.co/O5CWBu8PCv via @TanqeedOrg

How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor http://t.co/EOubTjttQI

[…] How the modern state creates and protects bonded labor. […]

[…] also gefährlichen Verhältnissen. In diese Verhältnisse gibt beispielsweise der Artikel How the State Sanctions Bonded Labor von Sarah Suhail in der Ausgabe September 2014 der Zeitschrift Tanqeed Einblick, der von modernen […]