On Thursday, July 3, Pakistani soldiers surrounded Chak 15/4 L, a village in the Punjab town of Okara, beginning an hour-long assault that resulted in the deaths of two tenant farmers, Mohammad Hasan and Haji Mohammad Noor, who were killed as they ran for cover. Dozens of peasant farmers were injured and 65 people were arrested as soldiers conducted house-by-house searches. The injured were taken into custody at the local Combined Military Hospital, where the authorities also held the bodies of the deceased for two days before releasing them to their families following a district-wide protest.

The assault on Chak 15 started at 4:00pm, when soldiers surrounded the village in armored cars and jeeps.

“I was resting in my house when I heard the hooter [masjid loudspeaker] alert,” said Mushtaq, a local leader of the Anjuman Mazarin Punjab (AMP). “The soldiers started firing by the time I ran out to the fields. They went house to house looking for AMP leaders. They were hitting women, children or anyone who got in the way. They broke in to people’s homes and snatched mobile phones and valuables. We were besieged by hundreds if not thousand soldiers on foot, in armored jeeps and trucks, it felt like we were in Kashmir or Palestine.”

The siege ended when the soldiers entered the village mosque and arrested the imam and the entire congregation, many of whom had gathered at the mosque seeking protection. At 5:00 p.m. the soldiers finally left the village and retreated to the Okara military cantonment, having left residents terrorised.

For their part, state authorities claimed that it was the tenant farmers who had opened fire on soldiers, after first blocking the canal water supply point in protest against a Rs 5,000 hike in rents. Tenant farmers and local activists agreed that they had blocked the canal, but vehemently denied firing any weapons at Army officers or soldiers. Some witnesses said that while the villagers did have weapons, they only fired them briefly into the air, and at a distance from the main group of villagers, to block soldiers from opening the canal.

As a tenant leader in Chak 15 recalled, the altercation began when a group of unarmed villagers confronted a group of soldiers who showed up at their village to force open the canal water channels. The tenant farmers resisted and the soldiers called in reinforcements, who descended on the village with the armored vehicles, and began firing machine guns at close range.

Continuing dispute

The Army’s attack on Chak 15/4 L opens up a new chapter in the continuing dispute between the Army and the AMP, and sheds light on the dangers of the cash contract system, the long history of dispossession under the pretext of national defence, and the use of counterterrorism laws to suppress livelihood struggles in Pakistan.

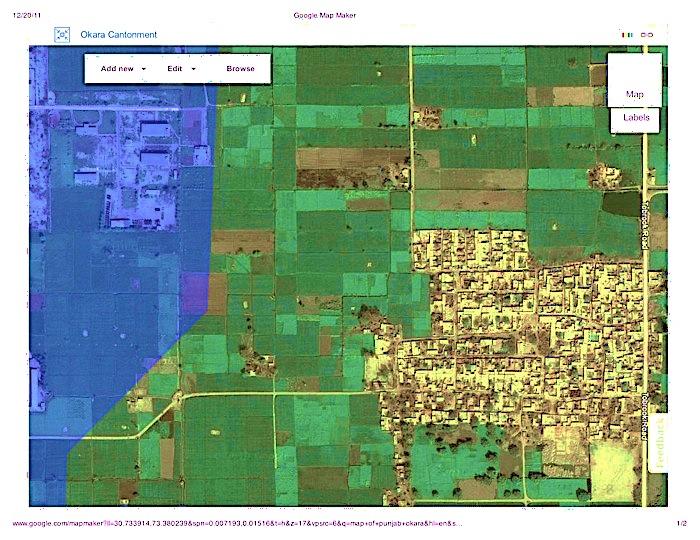

Chak 15 is located next to Okara cantonment, which is one of the largest cantonments in Pakistan.1 A large section of the cantonment encompasses farmland cultivated by tenant farmers, while the centre consists of high-priced bungalows, and common cantonment facilities like storehouses, a hospital and parade grounds. The latest standoff between the military and the tenant farmers started in late June, when the tenant farmers blocked the main canal water channel to Okara cantonment to protest against the rent increase, which would raise their annual contract rent to Rs 25, 000 per acre, an unsustainable sum for most subsistence farmers. The community’s leaders say the new rates are meant to evict the farmers altogether because this latest increase in rent makes it impossible to survive on the land.

“We work hard on this land. Our forefathers first settled these farms a hundred years ago in British times but look at our poverty, we can’t afford to buy shoes for our children […] we will have to leave this land if they raise the rent again, they [the Army officers in Okara cantonment] want to drive us out. It does not matter to them if our children starve or our animals die. They want this land for themselves and their friends,” explained Riaz Maqbool, an elder resident of Chak 15.

As an anthropologist who has been following the peasant protests in military farms for several years, I realize that the mazarin peasant struggle appears in the press in moments of altercation, when peasants are forced to take such dramatic actions as blocking canal water channels, or disrupting traffic on the Grand Trunk (GT) road. However, behind each dramatic confrontations is an overlooked story: one of the gradual building of violence, which gathers momentum until it has, almost imperceptibly to the outside world, brought farmers to the point of imminent dispossession.

Description: Chak 15 4/L and the edge of the Okara Cantonment (highlighted) | Source: Google Earth Maps

Up until 1999, all tenant farmers who worked on Pakistan Army military farms surrendered half of their crops in exchange for the right to live and work on the land under the pre-existing batai system (rent-in-kind payments).2 This sharecropping system came to an end in June 1999, when the Army instituted a cash contract lease system on all its farming estates. The vast majority of tenant famers rejected the cash contract lease system (thekadari) when they realized that these annual contracts would make them vulnerable to evictions. The tenants formed the AMP to collectively resist the imposition of this lease system and to demand permanent land use rights on lands their families have been tilling for a hundred years.

The current conflict involves those tenant farmers who live in the outskirts of Chak 15, whose ancestral villages (Chak 16 4/L, Chak 14 4/L, Chak 18 4/L) were razed when the Okara cantonment was first built in 1972. These tenants did not join AMP’s campaign against the cash contract system because they felt too vulnerable and they did not want to antagonize the Army.

“We did not want any trouble with the Army because we had already endured the pain of evictions when our homes were bulldozed to build the cantonment,” said Riaz, a tenant farmer who accepted the contract system. Hundreds of peasant households were forced to settle on the outskirts of neighboring farms, with some families settled in fields, animal sheds, and others opting to move to Gamber, a neighboring market town, where they continue make a living as day laborers. Others simply left the region.3

Today, the dramatic increase in the cost of land is making it difficult for many households to subsist with farming, and many have gone deep into debt by borrowing heavily from artis (market traders who also lend money), they say. Some farmers said that they are having a hard time feeding their families, as they are unable to make enough money to last through the season. Each incremental increase in rent results in the loss of tenancy by poorer households, and subsequently the tenants’ land is leased out on the market to Army officers or higher bidders from neighboring towns. Serving Army officers of all ranks in Okara Cantonment have been known to take up large section of the lands.

Description: Rubble remains of the homes that were torn down this past January | Photographer: Mubashir Rizvi

The current scenario demonstrates the foresight of AMP leaders, who predicted that the cash contract system was a step towards their dispossession. While most tenants who rejected the cash contracts system in Chak 15 have prospered greatly by reaping full harvests and selling their crops in the market, the cash contract leaseholders have fallen on hard times with excessive rent increases, restrictions and severe penalties. For example, cash paying tenants who were formerly displaced from Chak 16, are not allowed to build any proper shelters in on the outskirts Chak 15, where they have been living since they were displaced from their native village. This past January, the Army sent soldiers to knock down homes that the tenant farmers built to seek shelter from frigid winter weather conditions.

The expansion of the cantonment has also resulted in the loss of land for neighboring villages, say farmers. The Army has posted fences and check posts on tenants’ fields, thus taking their land into the jurisdiction of cantonment authorities and forcing tenants to pay rent for land whose ownership is disputed.

It was this expansion and growing uncertainty faced by cash contract farmers that brought the cash paying tenant farmers together with AMP members to jointly resist the cantonment authorities in a bid to secure some guarantees or to demand replacement land for tenant farmers outside the cantonment area.

Security as a pretext

In the last four years, the Okara cantonment authorities have used the deteriorating security situation in the country to cordon off the cantonment with barbed wire and a chain of of gated check-posts guarded by soldiers all along the cantonment’s perimeter. All tenant farmers whose fields lie behind the barbed wire are required to obtain a special ID from the Army authorities to enter and exit the cantonment to access their fields. The pass costs Rs 1,000 to make and it takes countless trips to the local councilor’s office and a signature from a Grade 18 officer for identity verification. The cantonment ID is mandatory for anyone to enter the fields: there are separate IDs for tenants, land workers, and tractor operators, and each member of a household has to carry their own ID card in order to gain access to their fields.

Each farmer or farm laborer is only allowed to enter and exit their field from a specific check post, noted on the back of their ID . There are, however, cases where farmers’ entry gates bear little correlation to their needs, in terms of their field locations and the locations of adjacent water wells and canals.

In addition to the check posts, members of the Military Intelligence (MI) can, and do, ask labourers for IDs at any time.

“These officers find so many ways to humiliate us. Is this not Pakistan? Are we not Pakistanis?” asked one village elder. “If so, why can’t we use our national ID card? Why do we need to get a special cantonment pass? They harass us for this pass which costs so much.”

Crossing through check posts can become an ordeal, locals say, particularly if there are visiting dignitaries at the cantonment, or if the guards are in the mood to hassle those going through over seemingly banal details. Others said that soldiers had, at times, demanded that women uncover their faces for identification. One farmer described the questioning process as “frustrating and humiliating”.

Moreover, when the cards expire (they are valid for only a year at time), it takes three months for new ones to be issued. In the interim, the farmers exist at the mercy of the check post guards.

The Okara cantonment authorities also place apparently random restrictions on what tenant farmers are permitted to grow on their land. For instance, this past year, the cantonment authorities banned tenant farmers from growing rice, fearing that wet rice fields would attract Dengue-carrying mosquitoes. The tenants are not allowed to grow cotton for fear of attracting certain bugs.

Tenant farmers can also be subject to other arbitrary commands. For example, Ashraf who is cultivating four acres of corn was ordered to take down his crops 15 days before they were fully ready so the cantonment authorities could build latrines for check post guards. This resulted in a heavy loss for the farmer, who had borrowed some Rs200,000 worth of fertilizer and pesticides for this crop.

Activists treated as ‘terrorists’

The violent military attack on tenant farmers on July 3, after several years of relative peace, is an ominous sign, and this event is more troubling given that it occurred two days after the passing of the Protection of Pakistan Act (PPA) in the National Assembly. Currently, the Army is reasserting itself as a force against extremism and terrorism, but the events at the Okara Military Farms show how these powers are used and abused against livelihood movements. In the past ten years, dozens of tenant farmers and AMP leaders have been charged with multiple ‘terrorism’ charges in local anti-terrorism courts. It might come as a surprise to some that counterterrorism bills appear to be are more easily applied against peasant farmers, labor union leaders, and journalists than they are against known militant groups like Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan, Lashkar-e-Tayyaba and their leaders, who operate openly throughout Pakistan.

Moreover, the rhetoric of “counterterrorism” fails to address the complex and multifaceted problems that confront Pakistanis today. It imposes silence on everyday forms of violence like the increasing rate of poverty, and food insecurity. The current state security discourse represents a major shift away from a class-based analysis to a clash of cultures, and from democratization to militarism. The rhetoric of terror evacuates the discussion of economic inequality and livelihood struggles that fuel popular discontent. Recent academic studies on Pakistan have focused largely on the rise of violence and the growth of religious sectarian networks. Missing in these analyses is a discussion of slow and residual forms of violence that lurks behind these developments. We know that extreme disparities of wealth, diminishing protections for peasant farmers, and large-scale displacement from the countryside have created great insecurity and uncertainty for most Pakistanis. With the PPA, the National Assembly has given the state more recourse to use a militarized response to poor peoples’ struggle for subsistence.

* The names of the farmers, villagers and AMP leaders quoted in this piece have been changed, to protect their identities.

Mubbashir Rizvi is an Assistant Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Georgetown University.

- The Army cantonment is another vestige of the British rule that has grown in proportion and role in postcolonial times. In colonial times, the cantonment served as a reserved area of land to separately house and discipline the troops from existing towns. It was made up of military residential houses, officers clubs, storehouses, offices, shooting ranges and parade grounds. Over time, many of these cantonments grew into major towns, urban centers with large markets consuming much of the produce of nearby countryside. Hence, the cantonment played a major role in the shift to commercial agriculture as it absorbed the surplus produce or helped bring the railway by which cotton, wheat, and sugar cane could be exported. A great proportion of spending on infrastructure of roads, and railways was built to link these military cantonments, and they became major garrison hubs for the colonial state. In contemporary times, many of the cantonment areas have been absorbed into large cities as posh localities or suburbs, even as continue to be used for military uses. [↩]

- As permanent tenants the tenant farmers claimed that they had a right to permanent land use rights (under the Punjab Tenancy Act of 1898), especially since this farmland belongs to the Government of Punjab, which leased the farms to the British Indian Army. Further correspondence with revenue officials revealed that the Army’s lease on this land expired long ago and the Army hasn’t been showing any revenue on these farmlands. Between 2003-2004, the tenant farmers faced severe repression from the military, police and paramilitary forces to force them to sign on the cash contract system. The tenant farmers were subjected to a campaign of repression, arbitrary arrest and “forced divorces’ for refusing to sign onto the new cash based tenure system (HRW 2004). The widespread international condemnation of tenants’ repression forced the Army to withdraw from using brutal extreme force, thus leaving the farmland to tenant farmers who continue to cultivate the land. However, those tenants whose fields lay behind the tenant. [↩]

- The Army established Okara cantonment after the 1965 war with India, when it realized its vulnerability after a ground invasion by the Indian Army. A string of new cantonments were built in eastern districts of Punjab along the Indian/Pakistan border. Much of the residential land was allotted to retiring soldiers and serving officers to give them greater stake in defending these lands in the case of possible invasion. Today, Okara cantonment occupies a huge chunk of the irrigated tracts in the district that is leased out to military officers who speculate in real estate or cultivate the farmland by hiring tenant farmers. Over the past forty years these cantonments have become a major source of real estate profits for retiring officers. However, this speculation comes at a price to village dwellers, peasants and sharecroppers who suddenly find themselves behind the expanding fence of the cantonment. [↩]

“The violent military attack on tenant farmers on July 3, after several years of relative peace, is an ominous… http://t.co/X2OcIzEbhW

On #Okara farmers and the practice of #dispossession in the name of #security | Our latest on TQ by Mubbashir Rizvi | http://t.co/aHHVlb7UOZ

RT @TanqeedOrg: On #Okara farmers and the practice of #dispossession in the name of #security | Our latest on TQ by Mubbashir Rizvi | http:…

RT @TanqeedOrg: On #Okara farmers and the practice of #dispossession in the name of #security | Our latest on TQ by Mubbashir Rizvi | http:…

Dispossession In The Name Of Security http://t.co/4CcGWJ10cs

Dispossession in the Name of Security- http://t.co/zZYwHj0blf Checkpoints/ BarbedWire/ Harassment in #Pakistan #Okara #landstruggle @GUAnthr

“@crunkistan: Dispossession in the Name of Security- http://t.co/8N2KBoQjA7 Checkpoints/ BarbedWire/ Harassment in #Pakistan #landstruggle”

“We were besieged by hundreds if not thousand soldiers on foot, in armored jeeps and trucks, it felt like we were… http://t.co/V7OLM9tSHw

RT @TanqeedOrg: “We were besieged by hundreds if not thousand soldiers on foot, in armored jeeps and trucks, it felt like we were… http:/…

[…] around Kalinjar and Gandhian is just one manifestation of a far broader dynamic in Pakistan: From Okara to Dera Bugti, the armed forces are acquiring and developing land around the country, sometimes […]