Please click on the tip jar and donate!

[purchase_link id=”7407″ color=”green” text=”Subscribe”]

Details HERE.

About us

Editors-in-Chief:

M. Ahmad & M. Tahir

Editors:

A. Hashim | A. Kamal | S. Hussain | S. Hyder | K. Hamzah Saif | K. Zipperer

Contributing Editors:

M. Kasana | R. Mehmood | I. Tipu Mehsud | H. Soofi

Urdu translators:

S. Bhatti | S. Hussein Changezi | S. Hussein | P. Mushtaq | A. Naz

Social media:

M. Kasana & K. Hamzah Saif

Interns:

P. Mushtaq | A. Naz

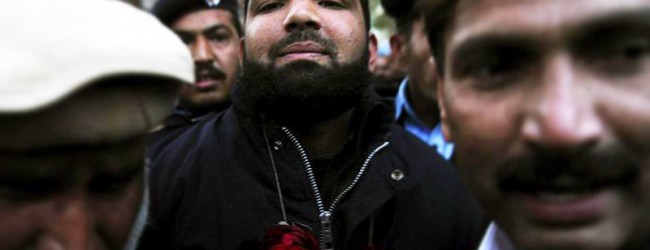

On Monday, the 9th of March 2015, Pakistan’s Islamabad High Court spattered out a mass of confusing, inconsistent, allegedly juridical statements upholding the conviction and death sentence of Mumtaz Qadri for the murder of then Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer.

A member of Taseer’s security contingent, Qadri flung out his state-granted weapon and shot the Governor an unrelenting 28 times for decrying Pakistan’s blasphemy laws. The act was condemned by some but celebrated by even more. After all, Taseer had called legislation designed to protect the dignity of a faith and a prophet a “black law”. In the eyes of his assailant and his assailant’s sympathizers, this verbal attack amounted to ‘blasphemy’—an unpardonable crime which can only be punished by capital punishment.

Taseer was a dead man walking.

The High Court’s denial of appeal has been lauded within the liberal ranks of the legal fraternity and beyond. There is no denying the judgment is brave in a country where courts are politicized, judges self-preserving, and society vociferously religious. At the same time, cries of victory have been stifled by the Court’s quashing of charges relating to terrorism that Qadri had previously been found guilty of by the Anti-Terrorism Court. As Qadri’s counsel, Justice Nazir, says to Dawn, this means “it will no longer be an offence to praise him (Qadri) [… since] glorifying a terrorism convict has become a cognizable offense” under the Protection of Pakistan Act. In a context where blasphemy reform is possibly on the cards, a moratorium on the death penalty has been lifted, and the government is set to execute Shafqat Hussain, convicted on terror charges at age 14 for his involvement in an alleged robbery, the High Court’s judgment is both crucial and terribly problematic.

And that might just be because it has been produced by a court struggling to reconcile its liberal legal edifice with a constitution and legal culture that is quasi-Islamic.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Like us? We survive on generous support from our readers.

———————————————————————————————————————————

That Pakistan’s legal infrastructure is inextricably linked to a particular, Sunni form of Islamic doctrine and jurisprudence is undeniable. Article 2(A) of the Constitution solidifies the Objectives Resolution (comically mistyped by the court as the “Objection Resolution”) into Pakistan’s constitutional framework and by doing so, establishes that the guiding principles of Islam will act as guiding principles for every lawmaker and interpreter in the land. The Federal Shariat Court ensures that a panel of eight pious Muslims will be ever-ready to strike down any legislation or policy that dares to contravene the injunctions of Islam. At first glance (indeed, after all subsequent glancing), it appears that Pakistan’s constitution arms the courts to adhere to the dictates of faith and dispense justice in line with the injunctions of their Islam.

That Pakistan’s judicial infrastructure has also been shaped by the colonizing forces of Western modernity—one that preaches to a different choir— is also undeniable. And herein lies the confusion.

The confrontation between two different modes of judicial thinking and interpretation are perhaps best illustrated by both parties’ main arguments before the High Court. Though the grab-bag of Qadri’s legal defense included the claim that he had been provoked into gunning down Taseer (and so, deserved a milder sentence) and that the state did not have compelling evidence to link him to the crime (aside, of course, from Qadri’s confession, multiple eye-witness accounts, 28 entry wounds, and bullets traced back to his weapon), his lawyers’ primary argument was a religious one. Salmaan Taseer was guilty of blasphemy. The state had not apprehended the infidel. The responsibility, therefore, fell on Qadri’s God-fearing shoulders to take action.

Qadri’s legal team focused on justifying the killing by drawing upon religious legal traditions highlighted by the Shariat Court, as well as civil cases related to blasphemy. It argued that the terrorism charges against Qadri should be dropped because rather than fear and panic, Qadri’s actions brought relief to the general public; a public that was terrified by the ‘messy utterances’ made by Taseer. Taseer was the real terrorist, Qadri a vigilante hero. Moreover, due to Shariah’s (divine law) precedence over ‘man-made’ laws, Qadri was morally correct even if his actions were extra-judicial in nature.

The state, on the other hand, sang a different tune—one that is more amenable to the sensibilities of contemporary legal communities and state institutions around the world. Speaking the language of fundamental rights and basic constitutional protections, the state had to systematically argue something many lawyers may take for granted—the accused named in Qadri’s defense, i.e. Salman Taseer, should have had his day in court.

Some in the print media are defending the court’s verdict, arguing that it ultimately upheld the modern tenets of due process and rule of law. On closer inspection of the judgment itself, it is difficult to maintain such conviction.

Firstly, the lengths the court goes to assess the arguments on Islamic grounds is disconcerting. Sifting through a haphazard plethora of Quranic verses and Hadith, the court cites a number of passages that seemingly corroborate Qadri’s claim—instances of the Prophet’s companions killing his “contemners” receiving retroactive divine sanction. Though ultimately proclaiming that no Muslim can resort to vigilantism, the court not only adds weight to the entire religious argument by assessing it on its own terms (and producing Islamic justification for it in the process), it is in a clear bind about which document to privilege—the constitution or the Quran.

This is most troublingly illustrated in the following excerpt from the court’s judgment:

“The plea of the appellant (Qadri) might have carried some weight if he would have made any effort to set the law in motion by reporting the alleged commission of the offence of blasphemy by the deceased and the different departments of the State designated to redress the grievances and dispensation of the justice would have failed to take the appropriate action against the deceased.”

“The plea of the appellant might have carried some weight”? It seems that the same court that goes on to declare that the subjugation of constitutionally-protected fundamental rights would result in “anarchy, lawlessness and rule of might is right” is making a very dangerous concession here. Had he complained to a relevant authority and had that authority not taken “appropriate” action, Qadri would have gone from being a controversial prisoner on death row to state-approved judge, jury and executioner.

Instead of getting right to the constitutional crux of the matter, the court spends forty pages examining the Islamic dimensions of Qadri’s contention. It is only at page 58 of a 64-page judgment that the court is shaken from its dreamy perusal of Islamic texts to say:

“It is also beyond our comprehension that how by declaring the act of appellant as “extra judicial” learned counsel describe(s) it in accordance with law?”

Exactly, Court. Why is this not enough?

———————————————————————————————————————————

We cannot survive without your support!

———————————————————————————————————————————

It is precisely because of the dual character of Pakistan’s legal system—Islamic and “modern”—that the court ends up tripping over itself time and again. And this juridical schizophrenia is best-described by the court itself:

“[…] but from whatever angles it is considered, neither the Islamic law nor the law of the land gives any justification of the act of the accused.”

“Neither the Islamic law nor the law of the land”. Two separate entities, both equally important.

When the court is not busy quoting a Quranic verse or narration from the Prophet’s life, it is searching for legitimacy from secular legal systems and societies to persuade the reader that it is possible to serve justice through the unorthodox combination of formal legal interpretation and normative religious guidance. It does this by attempting to humanize the blasphemy laws through deference to colonial legal systems:

“It is further observed that blasphemy is an offense which is recognized in every religion […] In the post-Restoration politics of 17th and 18th century England, Church and State were thought to stand or fall together. To cast doubt on the doctrine of established church or to deny the truth of the Christian faith upon which it was founded was to attach the fabric of society itself.”

Moreover, the court spends an inordinate amount of time highlighting the greatness of the Prophet by citing non-Islamic sources—a claim is made that the Prophet was mentioned by name in both the old and new testaments; Tolstoy, Napoleon and Rousseau are cited as notables from the Western world who have gone on record to extol the great man.

Blasphemy and Religious Minorities in Pakistan

Whether or not the Court’s tenuous balancing act between extra-judicial Islamic justification and orthodox common law reasoning is successful is up for debate. What is incontrovertibly true, however, is that this judgment has potentially devastating implications for some of Pakistan’s most vulnerable—religious minorities.

If the ecumenical greatness of Islam is to be expressed through the fact that ‘even the Prophet’s enemies respected him’, the court is implying (inadvertently as it might be) that respecting the Prophet is not enough to make it into the Muslim good-book. You can respect the Prophet but obedience to Islamic values as interpreted and propagated through the instruments of law is a prerequisite of citizenship in the Islamic Republic. Moreover, the court seems to suggest that it is not just Muslims who ought to respect their own Prophet, but all religions and sects.

This is particularly problematic when considering the wishy-washy linguistic interpretations the court attempts to make. For example, during the proceedings, the definition of blasphemy is derived from the Arabic words Shatam and Azi. They can be interpreted as to suffer, as in to make the prophet suffer. What causes sufferance, however, becomes quite controversial when possible meanings are relayed by the court:

“[…]to suffer, to harm, to molest, to contemn, to insult, to annoy, to irritate, to injure, to put to trouble, to malign, to degrade, to scoff.”

All these meanings can lead to different incriminations in any blasphemy case. Though it is commendable that the court denounces Qadri’s vigilantism, there is a great amount of collateral damage that stems from this legal battle. Pakistan’s minorities live on top of a volatile legal fault-line: the capricious interpretations of arcane traditions. ‘To annoy’ or ‘to irritate’ are extremely arbitrary crimes against a very strict law.

Our purpose is not to reiterate the obvious or oft-cited—that blasphemy laws disproportionately hurt religious minorities. The point, briefly put, is that a judgment that reaffirms the conviction of a murderer cannot be celebrated without closely examining its legal implications.

Firstly, the court’s equal treatment of formal legal machinery and extra-judicial Islamic injunctions is enough to trouble any minority. The law is virtually in a constant state of uncertainty—Islam, even those parts of it that are not explicitly codified, can be used to potentially justify even first-degree murder.

Secondly, the court repeatedly reaffirms the moral legitimacy and legal basis for the continued existence of the blasphemy law in Pakistan by proclaiming that the Pakistani State “has to protect the tenets of Islam (and so) introduced the legislation for the protection of the respect and dignity of the Holy Prophet”.

Thirdly, the court confidently declares that the crime of blasphemy can be met with no punishment other than death—“it cannot be compounded or forgiven by any complainant as the State is (the) custodian of protecting the honor and dignity of our last and beloved prophet Muhammad (P.B.U.H)”.

All this is happening at a time when the court should be reconsidering its stance, not reaffirming it. Recent work done by researchers and activists Arafat Mazhar and Zain Moulvi has highlighted various catastrophes in the historical lineage and evolution of the blasphemy law in Pakistan—work that has the potential to pose a monumental challenge to the mainstream narrative that blasphemy is an unpardonable crime that can only be met with the death penalty.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Want to read more essays like this one? Subscribe!

———————————————————————————————————————————

According to their research, revered scholars within the classical Islamic tradition like Abu Hanifa stated that “blasphemers who ask for a pardon would be spared the death penalty”. In general, the research uncovers a historical white-wash of theological dissent, disastrous historical misinterpretations, frivolous citations and off-the-record confessions by Ismail Qureshi—the architect behind this very law. The sources that are usually thrown around as untouchable evidence of the law’s immutability have in-built rebuttals for the people who employ them.

If the court had truly condemned Qadri’s vigilantism, it needed to spell out a schism between the constitutional purpose of the law and the religious intent behind it, because the confusing and rigid nature of the law formed a part of Qadri’s defence. On the surface, he seemed to say that he killed for God and for the state. If one reads between the lines, however, he is saying ‘ I did this for God, and so the state must protect me’. By putting Islam and the “law of the land” on equal footing, the court did little to dismiss this line of defence as the fantasy of a rogue vigilante.

Many would argue that the only appropriate venue for talk of reform of the blasphemy laws is the place of their creation—parliament. However, one cannot undermine the role courts play in influencing public perception over legal and policy debates. With a judgment like this, which mindlessly recites all of the myths surrounding the blasphemy laws, legal reform only becomes a more distant possibility.

Terrorism

A portion of the judgment that has been widely criticized is the quashing of terrorism charges against Qadri. What is perhaps more interesting than the dismissal itself is how casual it is—the court dedicates only a couple of paragraphs to reverse a decision made by a court that otherwise had jurisdiction to decide the matter. The court conducts a half-hearted qualitative analysis of “fear and panic” and nonchalantly concludes that the murder of one man could not have unsettled the masses. End of analysis.

Never mind the fact that the law states otherwise. According to Section 6(2)(n) of the Anti-Terrorism Act 1997, a terrorist action “involves serious violence against a member of the police force, armed forces, civil armed forces, or a public servant”. Predictably, this clause never finds it ways into the discussion.

This is especially startling when considering the myriad of offences Pakistani citizens (usually poor) are convicted for under the Act. Shafqat Hussain, convicted at age 14 for his alleged involvement in a robbery and murder, has been on death row for the last decade. According to recent editorials on the case, Hussain was arrested after the disappearance of a tenant in his building and was “illegally held, bound, blindfolded and beaten” for nine days, only to be coerced into signing a confession and “was tried, for reasons unknown, in a special anti-terrorist court where an appointed lawyer failed to ascertain his age or produce any defence witnesses”. He is scheduled to be hanged within the week, amid international uproar.

The story does not end with Hussain, however. Since the Pakistani government lifted the moratorium on the death penalty on December 17, 2014, 39 executions have been carried out with 12 of them taking place on a single Tuesday around the country. Many of those executed were found guilty for terror-related offences. In the cities of Karachi and Jhang, four men were hanged on March 17th for convictions of robbery and murder under the Anti-Terrorism Act.

It seems then, that murder can cause fear and panic—that it can, indeed, unsettle the masses. Our own judges look into the eyes of the downtrodden and tell them this before sending them to the gallows.

This is why the court’s careless treatment of Qadri’s terror conviction is both disappointing and dangerous. It does nothing to develop the law on the issue and so, deprives people like Shafqat Hussain from legal precedent to use in their favour. We are not suggesting that Qadri is a terrorist and should have been treated as such. We are merely illustrating the machinations of a court that goes out of its way to ignore precedent and black-letter law to let Qadri off the hook—even if it is only partially.

Could it be out of sympathy for a faithful man? Professional self-preservation? Animosity for the notoriously secular Taseer? Or worse, did the court just not care? In any case, the court’s treatment of Qadri’s terrorism conviction is yet another worrying facet of a judgment that many are all-too-swiftly deeming “heroic”.

The Islamabad High Court may have punished Qadri but it condemned Taseer. Tragically, by entertaining the possibility that Qadri could have been acquitted had he spun the wheels of justice in motion prior to killing the late Governor, the court has only scorned him for not making murderers out of us all. This is hardly reason to celebrate.

Aisha Ahmad is a Lahore-based lawyer, researcher, and graduate of Harvard Law School.

Farhad Mirza is a free-lance journalist, based in Lahore. He is a regular contributor to various publications in Pakistan, Kosovo and the UK.

more harm than good? it does no good at all. prime example of the high court pandering to the religious right.

If a legal redress exists, it should be used, I think the court was right. Unfortunately it should also be remembered that Taseer, being a governor, enjoyed immunity. Still, taking the law in one’s hands is unacceptable. But this article moves off to the argument of abolition of blasphemy laws, though in reality, what is needed is just their improvement in implementation. If denying the Holocaust can be declared a crime, so can this.

Did Qadri take the law in his hands? If so, he was at least morally right. But what law was broken by Taseer? Is there a law that forbids asking for a change or even abolition of the blasphemy law? A law, passed by the Pakistan national Assembly and not a divine ordnance.